La Ultima Cena- The Last Supper

In 1976 director Tomás Gutiérrez Alea released his film “La última cena” (The Last Supper), which is set on a sugar mill in Havana, Cuba at the end of the 18th century. Slavery is an important part of history during this time and in “La ultima cena” Alea tries to show the viewer the sordid imbalance of power between a slave and the slave owner and how religion plays a role in trying to ease their sufferings.

In 1976 director Tomás Gutiérrez Alea released his film “La última cena” (The Last Supper), which is set on a sugar mill in Havana, Cuba at the end of the 18th century. Slavery is an important part of history during this time and in “La ultima cena” Alea tries to show the viewer the sordid imbalance of power between a slave and the slave owner and how religion plays a role in trying to ease their sufferings.

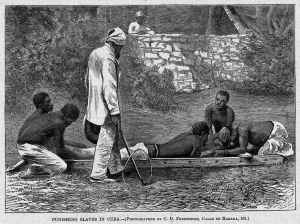

The movie begins with the plantation owner, a Count, returning after a long absence. It was not uncommon for plantation owners to be absent, and the daily responsibilities were left to the mayorales who were usually white and sadistic. Upon the Counts return, a slave has escaped and the mayoral Don Manuel is on the hunt for this repeat offender. When the runaway slave, Sebastian, is finally caught and brought back to the mill, Don Manuel decides to make an example of him and punishes him by cutting off his ear which he feeds to the dogs. This disgusts the Count but he accepts it as part of owning slaves. This act also shows the disregard for the slaves as people.

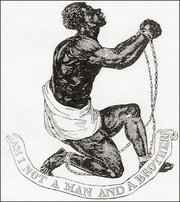

Holy Week, the last week of Lent in the Catholic religion has begun and the slaves have not been permitted to worship. The plantation priest tells the Count that the “blacks don’t understand Christian doctrine and they need to be allowed to go to church especially during Holy Week.” Slaveholders at this time do not feel the need to keep their religious responsibility. They are pressured to produce increasing amounts of sugar, so religion gets placed on the backburner, even though religion was used to help in slave management.

Not being able to find “peace” the Count decides to pay homage, so he orders Don Manuel to pick twelve slaves to join him for the ceremonies of Holy Week. This is the Count’s attempt to teach his slaves the values of obedience and endurance (Mraz) as well as possible reconciling with God. The Counts behavior is mocked by those around him as being nonsense and unproductive, and the slaves just look at him as being crazy. The chosen are then sent to the river to bathe. The priest is present at the river when the slaves are bathing- to the viewer it looks more like a baptism rather than a bath. When local women are found to be washing clothes topless the priest yells at them to leave, so they do not add to the sins of the slaves. After this baptism or cleansing the twelve slaves enter the home of the Count.

The Count tells the men that like Christ, he has called upon his friends, his disciples, his slaves. The Count then humbles himself before his slaves, by washing and kissing their feet, just as Jesus did to his disciples. However the viewer can see the Count’s feeling of superiority when he wipes his mouth after kissing their feet. The count then takes the twelve into the dinning room to simulate the Last Supper of Christ. He even goes as far as to act as Jesus, giving the twelve his body and blood just as Jesus did to his disciples. During the meal the Count becomes drunk and promises the slaves they will not have to work on Good Friday, and he also grants one of the older slaves his freedom without a coartacion.

This lesson in submission and endurance fails and the slaves revolt when asked to work on Good Friday. The slave’s revolt follows that of the revolt in Haiti. In 1791 tension was building on the French island of Haiti. French plantations on Haiti were known for their cruel conditions towards slaves. Slave populations in Haiti were huge due to the need for large amounts of labor for sugar and coffee production. As a result the slaves outnumbered the French.

On August 22, 1791 over one hundred thousand slaves under the leadership of Boukman rose up against the French citizens. These men and women wanted vengeance as well as freedom from the cruelties that they had suffered. Over the next three weeks plantations were burned, and Frenchmen were executed. The revolution would last for over twelve years and cost hundreds of thousands of lives. The Haitian Revolution would transform one of the most productive European colonies into an independent state run by former slaves. Ducle the French mill manager had warned the Count of this possibility but his warnings were dismissed.

Mraz wrote that “the way in which people experience the world is seen to be a function of their concrete historical situation; the forms in which they represent their experiences are understood to be expressions of particular class interests.” We see this in both the Count and the slaves. The Count saw himself as a fair and kind slave owner. However he wants his plantation to prosper, and that means the slaves have to work constantly, even on religious holidays. The Count’s Christian ideals mean nothing when it comes to making money, or treating his slaves cruelly.

The slaves experience in comparison to their owners was very different. Slaves had no rights. They could not vote, hold office, or even determine their future. Alejandro de la Fuente’s article, “Slaves and the Creation of Legal Rights in Cuba: Coartacion and Papel,” illustrates how slave owners got around the law. Slaves petitioned to get the price of their freedom, so that they may work to pay for themselves. These prices however would change or slave owners would not pay their slaves in order to keep them for longer periods of time. The slaves in the movie were not granted such recourse for the cruelties they encountered even though Cuba at this time had laws to prevent this. History has also shown that even though these laws existed enforcement was few and far between. The end of the movie shows this injustice when the rebel slaves are caught, given no trial, and their heads are placed on stakes to remind others of the consequences to their actions.

Robert Rosenstone has argued that to be considered historical, rather than simply a costume drama that uses the past as an exotic setting for romance and adventure, a film must engage, directly or obliquely, the issues, ideas, data, and arguments of the ongoing discourse of history.” (Mraz) “La última cena’s” portrayal of history was a fair depiction of history, and as Mraz stated it has opened a window into the past rather than constructing a particular version of it.